BLACK SHEEP @ THE 30th MONTREAL WORLD FILM FESTIVAL

Eight or nine years ago, I broke up with my first boyfriend. I thought I was doing alright. Turned out, not so much. I decided to take a much needed and deserved vacation. I had not taken one in a long time and did not really know what to do with myself as I had the time but not the cash to do anything or go anywhere significant. That was the summer I discovered the Montreal World Film Festival. I would escape my pain and my thoughts in the dark of the Parisian theatre, watching film after film until they all became one big movie and dizzying of my mind slowed.

Over the course of a week and a half, hundreds of movies play from morning until night. An occasional Hollywood offering makes an appearance but, for the most part, the films that make up the program come from all over the world. You either catch them at the festival or you never hear from them again. I no longer see so many movies all day that I can’t tell them apart. Depending on the year, I often end up seeing a dozen or so films. This year, I had no time off to speak of, so I was able to catch five films. This is an account of my journey around the world … the world film festival, that is.

Having whittled down the list to five films that met my interests and schedule, I was very excited to see my first selection, Germany’s SO LANGE DU HIER BIST (AS LONG AS YOU’RE HERE). My anticipation for the festival came to sudden halt, the kind that could leave you with whiplash, moments into this tediously drab film. Once my eyes had adjusted to the dark grain of the DV transfer that left many sequences indistinguishable, I saw that what I had left to focus on was awkward and uncomfortable, not to mention boring. The opening sequence of retired Georg gluing a broken teacup back together shows promise of a thoughtful film that will explore the reparations of a shattered life. Then the lights go out and the drastically younger, Sebastien, Georg’s regular prostitute, knocks on Georg’s door. Both live hermit-like lives, Georg in his apartment and Sebastien, on the street. They spend the remainder of the film trying to connect with each other and give meaning to a relationship that is almost as meaningless as their lives have become. The apartment setting is cold and cramped. The constant tight framing only further lends to the growing claustrophobia this film incites. While Sebastien sits under the kitchen table like a child, Georg records all their interactions onto a tape recorder. Trust me, you wouldn’t want to spend more than five minutes trapped in this dark apartment with these two. Luckily, the film only clocked in at an hour and twenty minutes. I was very happy to leave.

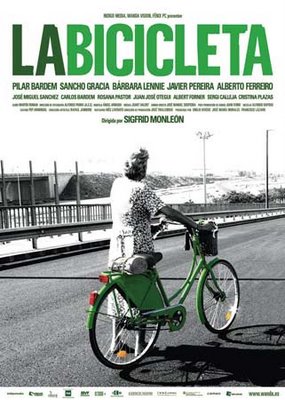

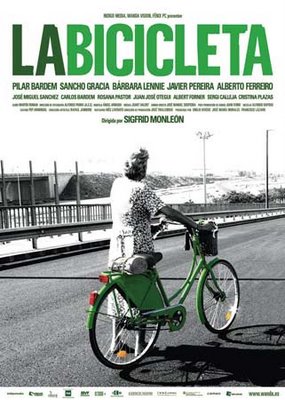

The next morning, I was subjected to write a DVD review for another horrible film, called SORRY, HATERS, which I had to watch twice because I am contracted to review the disc features. With the rain falling in sheets from the sky, I was not enthused to be trekking out to the festival again for another potential disaster. Though it was not shining outside, the sun was beating against my face with fortune inside the Quartier Latin cinema as I watched my second film, LA BICYCLETTA, from Spain. LA BICYCLETTA was a joyous celebration of love and life, a true bohemian crowd-pleaser. Three stories are told about three similar people at three very different stages of their lives. Their love and connection to their bicycles ties them together. There are occasional structural problems, as two of three main characters interact but the third never crosses anyone else’s path, but these are easily overshadowed by the messages director Sigfrid Monleon infuses into his film. The bicycle is a mode of transportation that is not merely controlled by the driver but also powered by the driver. It is an innocent vehicle that brings out a children’s ideology in all who ride it. It is inexpensive and environmentally sound, making all who ride them respectful equals. Aside from their love for bicycle riding, the three main characters are all pioneers and not followers, further enforcing the symbolism behind riding a bike and controlling your own destiny. 12-year-old boy, Ramon, doesn’t feel the need to fit in with the cool crowd; Young woman, Julia, is determined to make it in the big city; and retired mother, Aurora, doesn’t want to move from her home just so the city can redevelop the area. This breezy ride will make you feel like you too are on a bike, gliding down a hill with the wind blowing through your hair while the sun warms your skin. When I left the theatre, it had stopped raining.

My hump film and the last one I saw in a language I don’t speak was KEILLERS PARK, from Sweden. It did not take very long for this film to become a variation on a film subgenre I’ve seen far too often. Successful businessman and happy husband, Peter, makes eye contact with an attractive man on a city bus and his world is torn apart. He happens across the young man again a short time later and it is not long before he is naked in his arms. This is the first of the film’s plot holes as his new lover, Nassim, just finished saying how he wants nothing to do with helping a married man find himself. His wife finds out and leaves him; his sister finds out and calls him a dirty pervert; his father finds out and disowns him. All are tired story elements that one expects to happen. It predictably becomes Peter and Nassim against the world, powered by their deep love. The ignorant reactions of the people in Peter’s life feel like the painful film reactions towards gay people from a dozen years ago. In a 2006 film, they feel like leftover issues that taint the film in its own homophobic colour. Perhaps these issues are expected in a Swedish city but as a North American audience member, I’ve dealt with them all before and left them behind already. The rest of the film is marred by odd motivations. Peter doesn’t seem the least bit phased by the drastically new direction his life has taken. Even stranger is when Nassim suddenly turns on Peter out of nowhere and with no explanation. It is no wonder filmmaker, Susana Edwards, wrapped this flat story in a murder mystery blanket. Without that and some colourful imagery, KEILLORS PARK is nothing more than a revisiting of 90’s homophobia.

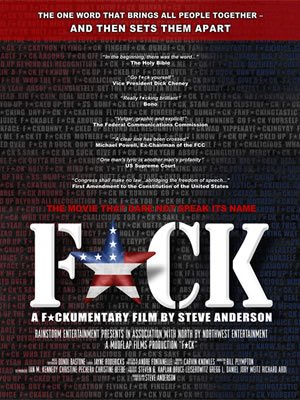

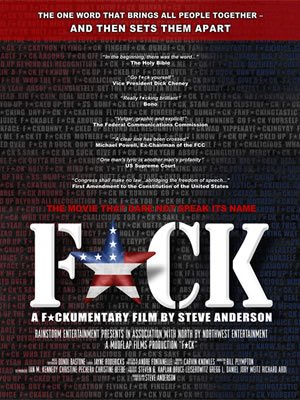

F is for Friday, Film and Fuck. I say this because on Friday, I saw a film documentary on the F-word. F is also for Flawed and Funny. These two words sum it all up. American documentary, FUCK, explores how one little four-letter word can satisfy so many expressions of emotion and anger so many conservatives. At times, the documentary seems too reliant upon other media to stand on its own, interspersing many clips from films and stand-up routines as examples of heavy F-word usage. Aside from the clips, the film bounces back and forth between streeters, talking heads and animated bits. The talking heads are a little off-colour and the streeters are a bit of a stretch at times. The film itself even strays off course when it gets more into attitudes towards sex instead of the word for having sex. All that aside, there are many laughs to be had and some good points to discuss. FUCK is most insightful when it deals with how those who use the F-word are generally considered to be of a lower class; how protecting the children of America has become a blanket excuse for increasing censorship; and how different intonations change the functionality of the word. When used the right way, the word itself ordinarily incites people to laugh when they hear it so you can imagine how many laughs there were in a film that has “fuck” said nearly 700 times.

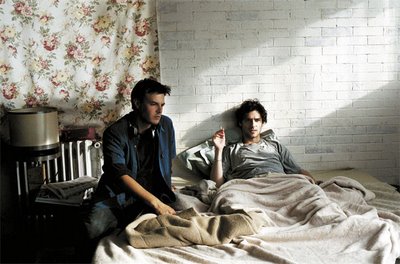

For my closing film, I chose to see the closing film of the festival, Canada’s own LA VIE SECRETE DES GENS HEUREUX (THE SECRET LIFE OF HAPPY PEOPLE). Quebecois director, Stephane Lapointe, tells the story of Thomas, a perpetual loser who is about to finish university at a fine school his father paid for in a program his father chose. The man cannot make his own decisions and has no idea what would make him happy. All he knows is that his successful businessman father, trivia genius mother and gifted sister have a much better handle on life than he does. Enter Audrey, a girl he meets on campus. For the first time, someone sees past his timid exterior to the warm person inside. The smiles beam from his face because now he doesn’t need to worry about his future anymore as he’s got a girl to distract him. From the moment the blueprint-style credits begin and flow into a cursive camera movement opening sequence at a family party, LA VIE SECRETE announces its arrival as a contemporary commentary on the pursuit of happiness. It is amusing, well acted and thoughtful. Disappointingly, the steam wears off before it reaches the halfway point. Odd, inexplicable scenes take you out of the flow and slow the film down until the bizarre explanation is given for these scenes. Not surprisingly, predictability settles in as the people who supposedly have life all figured out begin to unravel. Even Audrey, Thomas’ muse, transitions from character to caricature as her actions become less believable and more just the actions one would expect from a male writer who hasn’t quite figured out how to see a female character as anything more than a device to satisfy the male character needs. Despite not sharing any new insights on the secrets behind being happy, the film is light and enjoyable.

Light and enjoyable isn’t quite going out with a bang but from the sampling of films I ended up seeing at the World Film Festival, it seems a seriously impressive closer was not amidst the bunch. All the same, each year is always a gamble and as some of the films paid off, I still feel like a winner. Just having the opportunity to sift through so many possibilities and seeing the films with people that matter to me is enough to keep me coming back year after year. And though my initial reasons for finding the festival were to escape life, I no longer find myself running away but rather running towards.

(Thank you to Raymond, Holly, Josh, Samantha, Alexi and Trevor for joining me.)